The field of maxillofacial surgery, which masterfully blends medicine and dentistry to treat complex issues of the face, mouth, and jaw, seems like a pinnacle of modern science. With advanced 3D imaging, computer-guided surgery, and biocompatible implants, today’s surgeons can achieve results that were once unimaginable. However, the roots of this specialty stretch back thousands of years, built upon centuries of incremental progress, wartime necessity, and technological breakthroughs.

Understanding the history of maxillofacial surgery provides a profound appreciation for its current capabilities. This journey from ancient, rudimentary procedures to the highly sophisticated techniques used today showcases a relentless pursuit of restoring both function and form. This article explores the evolution of maxillofacial surgery, highlighting the key milestones that have shaped this critical medical discipline.

Ancient Beginnings: Early Attempts at Facial Repair

The desire to repair facial injuries and deformities is as old as civilization itself. The earliest evidence of facial surgery comes from ancient Egypt. The Edwin Smith Papyrus, a medical text dating back to around 1600 B.C., describes the diagnosis and treatment of various injuries, including jaw fractures. It details methods for manually repositioning a dislocated mandible and using sutures to close facial wounds, demonstrating a foundational understanding of facial anatomy and healing (National Library of Medicine – Edwin Smith Papyrus).

In ancient Greece and Rome, figures like Hippocrates and Celsus also documented techniques for managing facial trauma. They described using bandages and other devices to stabilize fractured jaws, often binding the teeth together with gold wire or linen thread—a precursor to modern intermaxillary fixation (British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery). While these early efforts were basic and performed without anesthesia or knowledge of germ theory, they laid the conceptual groundwork for treating the maxillofacial region.

The Renaissance and the Dawn of Modern Anatomy

The Renaissance brought a revolution in the understanding of human anatomy, which was crucial for advancing any surgical field. Andreas Vesalius’s groundbreaking work, “De humani corporis fabrica” (On the Fabric of the Human Body), published in 1543, provided incredibly detailed and accurate illustrations of human anatomy, including the complex structures of the skull, jaw, and facial muscles (National Library of Medicine – Andreas Vesalius). This newfound anatomical knowledge allowed surgeons to approach procedures with greater precision and understanding.

During this period, surgeons like Ambroise Paré, often called the father of modern surgery, made significant contributions (Science Museum Group – Ambroise Paré). He developed improved methods for treating battlefield wounds, including facial injuries. Paré was a pioneer in using ligatures to control bleeding instead of cauterization and designed early prosthetic devices to replace missing parts of the face, such as noses and ears, showcasing an early focus on restoring a patient’s appearance.

Wartime Innovation: The Birth of a Specialty

While progress was made over the subsequent centuries, the true catalyst for the development of modern maxillofacial surgery was war. The devastating facial injuries sustained by soldiers during World War I presented an unprecedented challenge. Traditional surgical methods were inadequate for treating the massive tissue loss and complex fractures caused by new and powerful weaponry.

In response, pioneering surgeons like Dr. Harold Gillies in the United Kingdom and Dr. Varaztad Kazanjian in the United States developed revolutionary techniques for facial reconstruction. Gillies established a dedicated facial injury hospital and is credited with inventing the tube pedicle flap, a method of transferring skin with its own blood supply from one part of the body to the face. This innovation allowed for the reconstruction of noses, lips, and cheeks with living tissue, a significant leap forward. According to the U.S. National Library of Medicine, these wartime advancements formed the bedrock of modern plastic and maxillofacial surgery.

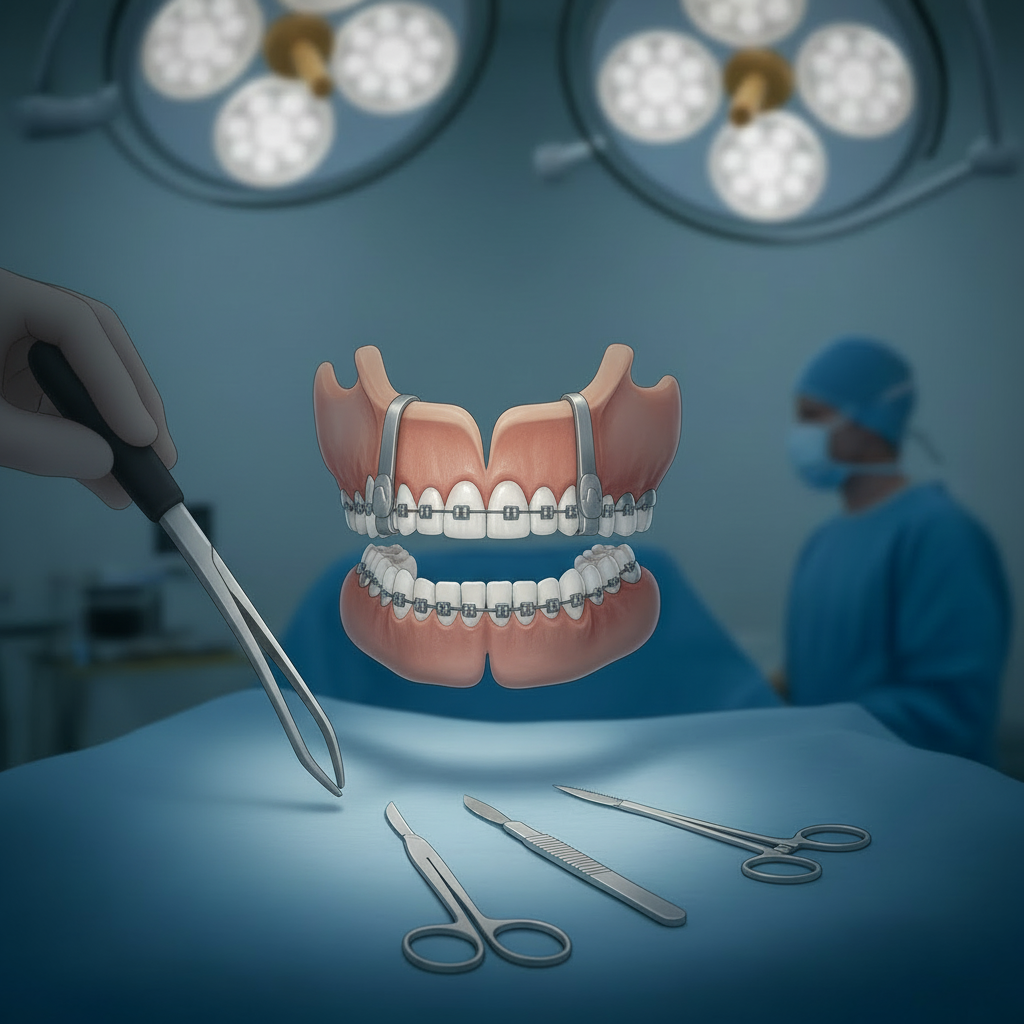

This era solidified maxillofacial surgery as a distinct specialty, bridging the gap between dentistry, which managed the bite, and medicine, which handled the surgery. The dual qualification of a Maxillofacial Surgeon, with degrees in both fields, emerged from this need for a comprehensive understanding of the entire facial structure.

The 20th Century: Anesthesia, Antibiotics, and Technology

The mid-20th century saw a series of breakthroughs that transformed all surgical fields, including maxillofacial surgery. The widespread availability of antibiotics dramatically reduced the risk of post-operative infection, which was once a major cause of surgical failure and death (CDC – History of Antibiotic Use). Advances in anesthesia made longer, more complex procedures possible, allowing surgeons to undertake extensive reconstructions with greater patient safety and comfort (NYU Langone Health – Anesthesia History).

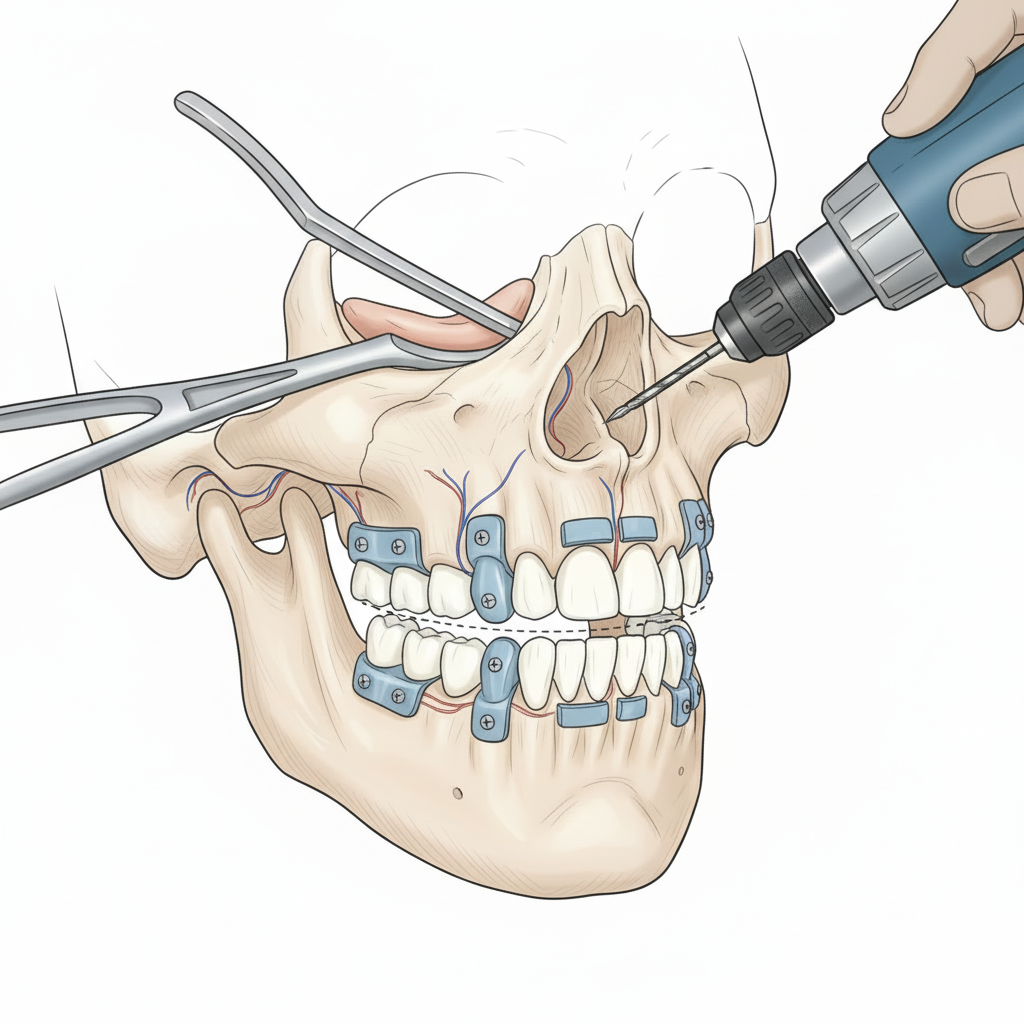

Another key development was the principle of rigid internal fixation. Swiss surgeons developed techniques using small titanium plates and screws to stabilize fractured bones. This method, detailed in numerous orthopedic and surgical journals, provided much greater stability than traditional wiring, leading to faster healing, better functional outcomes, and a quicker return to normal jaw function for patients (AO Foundation – History of Rigid Fixation). This technology was adapted for facial and jaw surgery and remains a cornerstone of orthognathic surgery and facial trauma repair today (National Library of Medicine – Facial Trauma Surgery).

The Digital Revolution: Computer-Guided Precision

The late 20th and early 21st centuries have been defined by the integration of digital technology into maxillofacial surgery, leading to a new era of precision and predictability.

3D Imaging and Virtual Surgical Planning

The advent of Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) provides surgeons with highly detailed, three-dimensional images of a patient’s skull, jaw, and soft tissues (RadiologyInfo.org – CBCT). This technology allows for incredibly precise diagnoses. More importantly, it enables virtual surgical planning (VSP).

Using specialized software, a surgeon can perform the entire operation on a computer model of the patient’s skull before ever entering the operating room. They can plan the exact cuts, reposition bone segments with sub-millimeter accuracy, and even 3D print custom surgical guides and plates. This level of planning minimizes surprises during surgery, reduces operating time, and improves the accuracy and predictability of the outcome, especially in complex jaw realignment (orthognathic) and reconstructive procedures (Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery – VSP).

Custom Implants and Biologics

3D printing technology has also revolutionized the creation of patient-specific implants. For patients with severe trauma, congenital deformities, or those needing total joint replacements for TMJ disorders, surgeons can design and print custom implants that fit the patient’s anatomy perfectly (Nature – Custom Implants in Maxillofacial Surgery). This leads to better functional and aesthetic results compared to off-the-shelf implants.

Furthermore, advancements in biologics, such as bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), are changing how surgeons approach bone grafting (FDA – Bone Morphogenetic Proteins). These growth factors can stimulate the body’s own cells to form new bone, sometimes eliminating the need to harvest bone from another part of the patient’s body.

The Future of Maxillofacial Surgery

The evolution of maxillofacial surgery is far from over. The future likely holds even greater integration of robotics for enhanced precision, the use of tissue engineering to grow new cartilage or bone, and further advancements in minimally invasive techniques that reduce recovery time and scarring (National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering – Tissue Engineering).

From ancient Egyptians setting jaws to modern surgeons using virtual reality, the goal of maxillofacial surgery has remained constant: to restore function, alleviate pain, and improve the quality of life for patients. The incredible progress made over millennia is a testament to human ingenuity and a deep-seated desire to mend what has been broken and restore what has been lost.