Airway Evaluation for Concomitant Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ) and Orthognathic (Corrective Jaw) Surgery

Evaluation for TMJ and corrective jaw surgery includes airway evaluation of the oropharyngeal airway and obstructive sleep apnea issues.

A common symptom in patients requiring orthognathic surgery, particularly those with an A-P deficient maxilla and mandible, is a decreased oropharyngeal airway and obstructive sleep apnea issues. Patients with TMJ issues, particularly those with condylar resorption pathologies, may commonly experience progressively worsening breathing and sleep apnea issues.

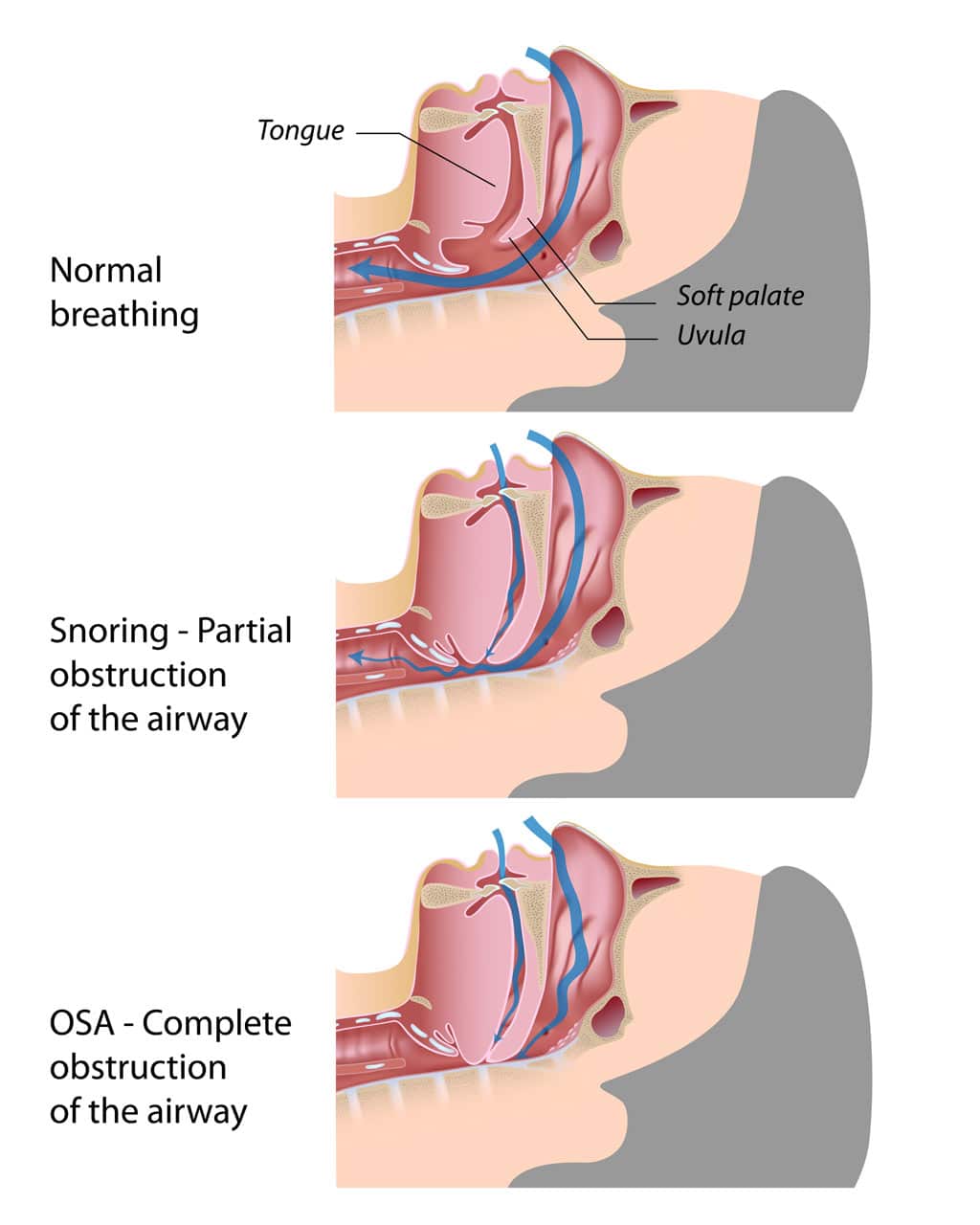

Obstructive sleep apnea is a condition with a minimum of 30 recurrent episodes during a 7-hour sleep period of functional pharyngeal airway obstruction lasting at least 10 seconds each. Some conditions associated with sleep apnea include:

- Daytime Somnolence with Sleep Apnea

- Recurrent episodes of cessation of breathing while sleeping

- Frequent awakenings and restless sleep

- Snoring and mouth breathing

- Nightmares

- Daytime somnolence (sleepiness)

- Poor work and school performance

Airway Evaluation Questionnaire for Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA)

Medical conditions that can be initiated by sleep apnea include high blood pressure, cardiac arrhythmias, right-sided heart failure, pulmonary hypertension, carbon dioxide retention, cyanosis, polycythemia, and premature predisposition to stroke, heart attack, and early death.

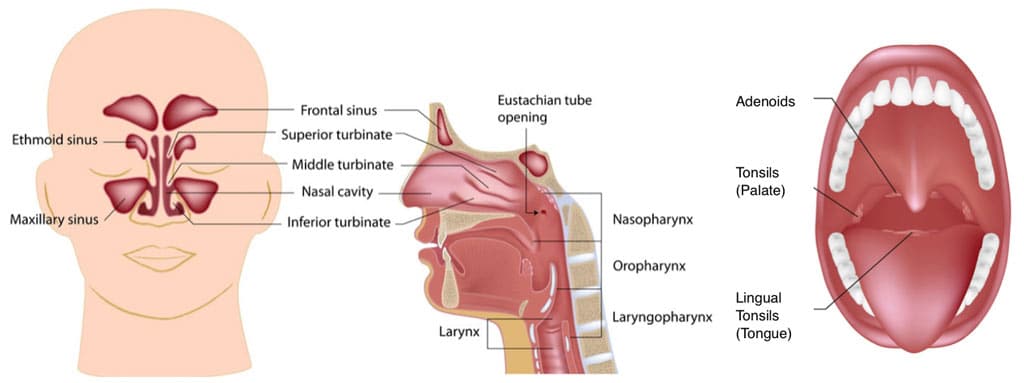

One of the most common areas contributing to sleep apnea is a decrease in the oropharyngeal airway. However, there are other major areas that can contribute to airway obstruction including the nasal airway, the oral cavity, as well as other anatomical structures in the oropharyngeal airway, such as tonsils, adenoid tissue, hyperplastic soft palate, uvula, etc.

Upper airway obstruction can have significant adverse effects on facial growth and development when occurring in growing children creating an increased vertical facial growth pattern with downward and backward growth vectors for the maxilla and mandible. Upper airway obstruction can affect the health and well being of children and adults afflicted with this anatomical variance of obstruction and can create functional and aesthetic facial, skeletal, muscular, and dental imbalances.

Nasal Airway Obstruction

There are a number of anatomical factors that can contribute to nasal airway obstruction including the following:

- Narrow nostrils

- Wide Columella

- Constricture of luminal (nasal) valves

- Transverse collapse of nose

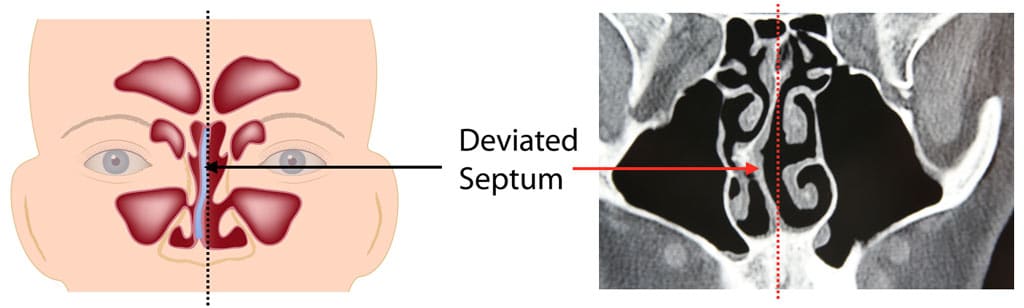

- Deviated nasal septum

- Hypertrophied turbinates

- Nasopharyngeal adenoid tissue

- Other anatomical variances and pathologies

Nasal Airway Evaluation

Clinical, radiographic, fiberoptic scoping, etc. are methods for evaluating nasal airway obstruction. Airway Evaluation begins by assessing the nasal width of the nostrils and columella. A nasal speculum can be used to evaluate the luminal nasal valves inside the nose and to evaluate the anterior aspect of the turbinates and nasal septum.

One of the most common forms of nasal obstruction is hypertrophied turbinates. The turbinates are a honeycombed bony structure covered with glandular and erectile tissues covered with ciliated mucosa. When these turbinates are enlarged, and/or septum is deviated or spurring is present, this can cause significant nasal airway obstruction. Usually laying down at night will cause increased swelling of the turbinates, further blocking off the functional airway.

Allergic rhinitis is a common contribution to nasal obstruction. Hypertrophied turbinates are the most common factor causing nasal airway obstruction. A deviated nasal septum also can cause significant obstruction as well as bending the nose off to one side or the other or with septal spurs that may be present. Nasopharyngeal adenoid tissue can cause a major blockage of the nasopharynx and posterior nasal choanae. This can be a problem in young kids, although adenoid tissues are usually resorbed by the age of 12 to 13, but may remain present in some patients for many years longer.

Oral Airway Obstruction

Oral airway obstruction can include any of the following factors:

- Transverse narrow dental arches,

- Retruded or A-P hypoplastic maxilla and mandible,

- Macroglossia,

- Oral tumors or other enlarging pathologies, and

- Large mandibular or palatal tori.

Transverse narrow dental arches displace the tongue posteriorly. Narrow dental arches, particularly the upper arch, are commonly seen in patients with nasal airway obstruction causing chronic mouth breathing and a downward and backward vector of facial growth.

Large mandibular tori can occupy a significant portion of oral floor of the mouth displacing the tongue upwards and backwards. Likewise, large palatal tori can displace the tongue downwards and backwards.

Macroglossia comes in 2 forms:

- Pseudomacroglossia is where the normal-sized tongue is relatively large compared to a decreased oral cavity space commonly related to a retruded maxilla and mandible causing the tongue to be displaced posteriorly thus decreasing the oropharyngeal airway. In this situation, if the maxilla and mandible are advanced forward with osteotomies, this increases the oral cavity volume and allows the tongue to function further forward in a more normal position and increase the oropharyngeal space.

- True macroglossia involves a tongue that is too large for the normal-sized oral cavity. This can be caused by a genetically enlarged tongue, over-development of the tongue by parafunctional habits versus pathological processes that enlarge the size of the tongue. With true macroglossia, patients often demonstrate anterior open bites, wide maxillary and mandibular arches, as well as diastemas between and over-angulation of the anterior teeth.

Oropharyngeal Airway Obstruction

Common factors that contribute to airway obstruction of the oropharyngeal area include:

- Elongated (hyperplastic) soft palate

- Hypertrophied uvula

- Con-stricture of the fascial pillars

- Hypertrophied tonsils

- Hypertrophied adenoid tissue

- Decreased oropharyngeal airway

- Tumors or other pathologies decreasing the oropharyngeal airway

- Pharyngeal flaps (in cleft palate patients)

A hyperplastic soft palate and uvula can contribute significantly to oropharyngeal airway obstruction acting as a valve blocking the nasal airway. An enlarged uvula can act as a vibrating structure contributing to snoring, as can an elongated flaccid soft palate.

Hypertrophied tonsils also can contribute significantly to oropharyngeal airway obstruction. Particularly those that suffer from recurrent infections can cause further enlargement making it difficult to breathe through the nose or mouth. Hypertrophied tonsils and hypertrophied adenoid tissues often go together, providing a significant mechanical obstruction.

One of the primary factors contributing to sleep apnea is a decreased oropharyngeal airway. The normal anterior-posterior dimension from the posterior pharyngeal wall to the soft palate and posterior pharyngeal wall to the base of the tongue should be 11 mm, plus or minus 2 mm.

In patients who have a retruded maxilla and mandible, this airway may be significantly decreased.Accompanying these deficiencies is usually a high occlusal plane angle. A normal occlusal plane to the Frankfort horizontal plane is 8 degrees, plus or minus 4 degrees, but commonly with a retruded maxilla and mandible, the occlusal plane is significantly increased making it more challenging to correct and open the oropharyngeal airway.

There is a triad of factors that commonly go together and they include:

- A high occlusal plane angle associated with retruded maxilla and mandible

- Nasal airway obstruction related to hypertrophied turbinates and/or nasal septal deviation or spurring

- TMJ pathology

Patients with the high occlusal plane angle facial morphology with a retruded maxilla and mandible should always be assessed for nasal airway obstruction, decreased oropharyngeal airway, and TMJ pathology.

In cephalometric analyses, maxillary depth, mandibular depth and the Frankfort horizontal plane must be established. Unfortunately, the Frankfort horizontal plane bony landmarks will oftentimes lead to a misinterpretation of the actual facial deformity.

Therefore, construction of a Frankfort horizontal plane ignoring the normal anatomic landmarks may be necessary to adjust the maxillary depth and mandibular depth so that numerically those numbers match the clinician’s impression of the patient’s profile. This then allows the use of normal anatomical cephalometric interrelationships to be used to establish good facial and occlusal harmony and balance.

The oropharyngeal airways and nasal airways can also be evaluated with the imaging.

A collection of all this data will aid the clinician in determining the presence of a TMJ condition, the severity, longevity, age of onset, and whether there are other systemic problems that could be contributory.